On a drizzly weekday near a council depot, a row of timber panels leaned against a wire mesh, their bases crumbling and their once-straight tops sagging slightly like tired shoulders at the end of a long shift. Nearby, stacked in rigid bundles, sat dark recycled plastic posts, each one straight, dense and faintly glossy, waiting for the next maintenance round along the riverside footpath. The contrast was quietly striking: one pile clearly at the end of its story, the other ready to stand in for decades with hardly any fuss. For crews planning their day, the choice between them is starting to feel less like an experiment and more like common sense.

Recycled plastic fencing begins life in a place few people want to think about for long: the sorting lines where mixed bottles, trays and film arrive in a restless stream. By leveraging finely tuned screening and shredding equipment, operators turn that unruly flow into a consistent plastic crumb that can actually be worked with. The flakes are then washed in closed-loop systems that reuse water again and again, keeping resource use significantly reduced compared to conventional plastic manufacturing. Melted and extruded into solid profiles, the plastic reappears as posts and rails that look unremarkable at a distance yet have been quietly transforming expectations about how long a fence can last.

Over the past decade, conversations with farmers and facilities managers have highlighted the same frustration: posts rotting off at ground level long before anyone feels ready to budget for a full replacement. A timber post set directly into damp soil will eventually lose its fight against fungi and moisture, no matter how zealously it was treated at the start. Recycled plastic posts, by contrast, shrug off that ground contact, behaving more like ceramic than wood when it comes to decay. The effect is a bit like swapping a flimsy umbrella for a sturdy, storm-rated model; once you have something exceptionally durable, you notice how often the older versions failed.

Maintenance tells another part of the story that is often left off glossy brochures yet matters enormously for the environment. Traditional fences usually rely on stains, preservatives and sometimes insecticides to stay presentable, creating a recurring cycle of tins, brushes and chemical run-off every few years. By integrating fencing that never needs those coatings, estates and councils avoid a surprising amount of solvent and pigment drifting into soil and drains. Recycled plastic fence lines stay more or less the same shade year after year, needing only a bucket of soapy water after a muddy season, a routine that feels highly efficient compared to the ladder-and-paint routine many households know too well.

A detail that reassures sceptical neighbours is how these fences look when installed, because early plastic products did not always blend gracefully into gardens and fields. Modern recycled profiles mimic the proportions and silhouettes of familiar picket or post-and-rail designs, so at a quick glance they seem strikingly similar to freshly treated timber. Only up close does the subtle texture give them away, and even then the difference can feel more like comparing ceramic to wood than plastic to anything cheap or flimsy. For homeowners who care about the view from the kitchen window, that balance of function and appearance is particularly beneficial.

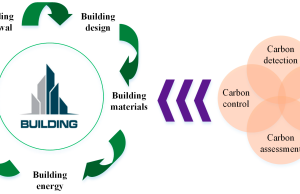

In the context of rising emissions and shrinking municipal budgets, the carbon story behind fencing materials is gaining more attention than it once did. Harvested timber from responsibly managed forests does store carbon and can perform extremely reliably when paired with clever sleeves and careful installation, so this is not a simple tale of good versus bad. Yet many fences still go up using timber with unknown origins, treated with cocktails of chemicals that make eventual disposal complicated. Recycled plastic fencing does not pretend to erase those dilemmas, but it channels stubborn, long-lived plastic into service in a way that feels remarkably effective when compared with leaving it to drift through waterways or sit in open dumps.

Watching a maintenance crew replace a line of splintering wooden rails with slate-grey recycled posts one blustery afternoon, I remember feeling an unexpectedly strong sense that this quiet swap said more about our environmental priorities than any official slogan on the depot wall.

Concerns about microplastics understandably hover over any suggestion to use more plastic outdoors, especially on routes where people walk dogs or children drag hands along rails out of habit. Here design decisions matter: dense, solid profiles that do not flake or crack under normal use shed far less material than thin cladding or decorative trims. Some manufacturers go further, offering take-back schemes so old posts can be shredded and remade, effectively keeping that material in a controlled loop rather than scattering it like confetti. It is not a flawless system, yet it is notably improved compared with simply burying mixed plastic and hoping for the best.

For medium-sized councils managing country parks, school grounds and cycle paths, recycled plastic fencing has become an incredibly versatile tool that joins benches, decking and signage in a wider shift toward durable materials. Along a windswept boardwalk, for instance, salty spray and constant footfall used to chew through timber handrails with depressing speed. With recycled plastic posts in place, the same stretch can stay intact for years, giving visitors a safer grip while staff focus on other jobs instead of endlessly patching rails. The result is a setting that feels quietly cared for, without crews buzzing frantically like a swarm of bees around the same failure points.

On farms, the environmental benefits become vivid whenever the land stays wet for long spells and wooden stakes simply cannot cope. A run of recycled plastic post-and-rail along a gateway, resisting the slurry and tractor nudges that usually finish timber, effectively protects both animals and hedgerows. Those hedges, given steady protection, can thicken into wildlife corridors that are particularly innovative in how they stitch fragmented habitats together. Here the fence is not just a boundary; it is a long-term scaffold allowing natural features to flourish while cutting the number of replacement posts trundling in on flatbed trucks.

For early-stage projects on tight budgets, the higher initial price tag can look daunting, which is why whole-life costing is so important to put firmly on the table. Once labour, repeat materials and lost time are factored in over twenty or thirty years, recycled plastic fences often turn out to be surprisingly affordable. A line of posts that simply stands there doing its job, year after year, becomes an extremely reliable ally for anyone juggling maintenance lists that never seem to end. In financial reports and informal chats alike, managers describe the relief of knowing a fence put in this year will almost certainly outlast several budget cycles.

Material choice also shapes daily experience in small yet meaningful ways that are easy to underestimate. Parents pushing buggies along a riverside path notice when rails no longer leave flaky paint on mittened hands. Volunteers clearing litter under a school boundary see fewer splinters, and grounds staff mowing near edges appreciate posts that do not shatter the first time a strimmer gets too close. These details add up, creating places that feel cared for and, just as importantly, are easier to keep that way without constant patching.

In the coming years, pressure to cut emissions and waste will only intensify, pushing every part of built infrastructure to carry more environmental weight than it once did. Fences may seem mundane compared with solar panels or electric buses, yet they occupy miles of streets, fields and shorelines. Choosing versions that divert plastic from dumps, avoid repeat treatments and stand up calmly to harsh conditions is a modest step with quietly multiplying effects. Each recycled plastic post hammered into place takes a little pressure off forests, paint factories and landfills, creating a chain of savings that runs far beyond the boundary it marks.

Walk past one of these fences on a wet evening and it barely demands attention; it just runs along the verge, solid and unremarkable, keeping its line where older panels might already have leaned or snapped. That unshowy reliability is precisely why more farmers, councils and householders are starting to specify recycled plastic without fanfare, treating it as the practical upgrade that it is. In doing so, they are not just tidying up a boundary; they are quietly voting for materials that last longer, waste less and fit more comfortably with the future most people say they want.