Quietly humming behind many of the newest developments across the UK is a question most clients and many designers don’t ask until very late in the process: “Can we prove this is zero carbon?” A phrase once confined to sustainability reports and green briefs has become a decision‑point — and a dividing line — for projects that will attract capital, tenants, and public trust.

When people talk about zero‑carbon certification in the UK today, they’re talking about more than a badge on a brochure. They’re talking about a rigorous process that binds data, design, energy and materials together into something measurable and defendable. In other words, it is an answer to a long‑standing problem: how do you separate genuine sustainability from well‑meaning rhetoric?

The new frameworks emerging here — built through years of industry collaboration — are not just technical. They are political and economic. They reflect rising expectations from investors, regulators and communities that buildings contribute less to the climate emergency rather than just “less than before.” The stakes are becoming real. Performance counts. Outcomes matter.

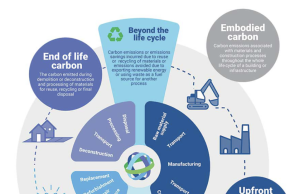

The essence of zero‑carbon certification is simple to state but hard to achieve: a building’s carbon emissions must balance to zero over its lifetime, down to the embodied carbon in its materials and the energy it consumes once people start using it. For most of my career, we spoke mostly about operational energy — how efficiently a building runs once built. Now we talk equally about embodied carbon. That’s the carbon embedded in every brick and beam, every drop of concrete and pound of steel — the unseen weight of our choices. A certificate acknowledges both; it requires measurement, reduction and, where any residual emissions exist, credible offsets or renewable energy generation.

Certification means more than meeting a standard. It means embracing a process. Projects that pursue a carbon label must collect data from the earliest sketch through occupancy, and verify that data independently. There’s a year of performance reporting after a building opens. Teams pore over energy consumption, onsite generation, and renewable integration. They measure emissions at each stage and compare them to science‑based targets that align with national and global climate goals. Some of the first projects chasing these outcomes struggled under the weight of spreadsheets, modelling software and late‑night meetings about insulation values and heat pump choice. Yet those struggles tell you something: the industry is no longer content with vague claims. They want proof.

I once attended a briefing where a developer announced proudly that their building was “net zero.” The room clapped. Then a carbon expert asked, quietly but directly, what standard the claim was certified to and what actual operational data supported it. The applause stopped. That silence — the uneasy pause — was telling.

This is why carbon building labels matter. They create a common language for projects, investors and the public. They help answer questions like: Has this building truly reduced its carbon footprint? Did it simply buy offsets instead of making real cuts? What is the balance between embodied and operational emissions? These are not academic concerns. They affect asset value, planning approvals, investor confidence and tenant decisions.

The move toward certification also reflects a shift in risk perception. In the past, developers worried about energy prices and planning conditions. Now they worry about carbon performance litigation, regulatory changes, and the reputational risk of claims that might later be challenged. A label backed by credible measurement helps manage that risk. It tells stakeholders that a project isn’t just compliant with regulations but aligned with evolving expectations that will shape markets for decades.

Yet the pursuit of a zero‑carbon certificate isn’t purely defensive. Some teams have found a kind of creative energy in the challenge. Architects who once saw sustainability as an add‑on are now rebuilding design approaches from first principles, thinking about massing, orientation, materials and systems integration holistically rather than as a checklist. Engineers talk earlier with planners. Clients push for embodied carbon reduction before seeing the first structural drawing. That shift, subtle as it is, feels like a recalibration not just of priorities but of professional identity.

There are bumps in the road. Standards are still evolving. Hard data on performance is lagging. Many certification schemes are voluntary, and some critics wonder if labels risk becoming marketing tools rather than meaningful benchmarks. Debate about offsetting versus reduction still rages. Some teams bristle at the cost and complexity. Others quietly admit that the metrics have made their projects better — more thoughtful, resilient and attuned to future regulatory pressures.

Much of the early work in certification has leaned on broader, international frameworks and industry collaboration developed over years. Now, UK‑specific standards are taking shape, responding to domestic policy goals and the shared understanding that the built environment accounts for a large chunk of the nation’s carbon emissions. These frameworks aren’t static; they are living, expanding as evidence accumulates, and as performance targets tighten toward long‑term climate commitments.

For clients, certification offers a yardstick for investment decisions. A building with a credible carbon label often attracts attention from institutional investors and occupiers who are under pressure to meet their own environmental targets. Lenders are starting to ask for evidence of carbon performance in underwriting. Tenants want certainty that their future energy costs and reputational risks are aligned with their own commitments to sustainability. A certified zero carbon label is like proof of performance — not a guarantee, but a signal that someone, somewhere checked the numbers.

Some designers still recall the early days of sustainability awards and voluntary ratings that felt more aspirational than exacting. They remember presentations where words like “green” and “sustainable” were used loosely. There was a time when a few solar panels were enough to earn praise. Now, zero‑carbon certification is pushing the industry beyond symbolism into accountability.

The real change — and what makes this moment notable — isn’t just that buildings can be certified as zero carbon. It’s that the conversation has shifted from whether it’s a worthy goal to how you get there, how you measure it, and how you prove it without ambiguity. This change matters because it influences how projects are designed, financed, constructed and operated long after the ribbon cutting.

Often, when we talk about climate action in buildings, we talk about grand visions. But certification brings the discussion down to concrete steps and real outcomes that people can see, compare and trust.