The British building sector has never been short of ambition; what it has often lacked is coordination. For decades, energy efficiency in homes and offices sat somewhere between aspiration and afterthought, tucked into planning documents but rarely enforced with urgency. That has changed. The UK carbon targets building agenda is now less about distant pledges and more about measurable deadlines, compliance documents, and invoices that land on property owners’ desks.

The most visible shift has been regulatory. Building Regulations have tightened in stages, each revision nudging new construction toward lower operational emissions. Developers grumble about cost, but many quietly admit the direction of travel is clear. The Future Homes Standard, scheduled to shape all new homes to be “zero-carbon ready,” is already influencing designs on drawing boards. Gas boilers, once automatic, are now debated line items. Heat pumps appear in plans where chimneys used to be.

What makes the net zero strategy UK approach distinctive is that it leans heavily on standards rather than symbolism. Instead of grand architectural gestures, it pushes insulation thickness, airtightness scores, and energy performance certificates. It is paperwork-heavy climate policy, which is probably why it works better than speeches. A site inspector with a checklist can change outcomes faster than a manifesto.

Walk through a new housing development outside Manchester or Bristol and you can see the incrementalism at work. Thicker walls. Triple glazing. Mechanical ventilation units tucked into utility cupboards. Nothing flashy, nothing particularly photogenic. Yet each element trims energy demand. The effect is cumulative, like compound interest applied to kilowatt-hours.

Existing buildings are a harder story. Britain’s housing stock is old, draughty, and emotionally protected. Retrofit is where carbon targets meet cultural resistance. Homeowners will tolerate scaffolding for a loft conversion, but not always for external wall insulation that changes a façade. The government’s retrofit schemes have had mixed reputations — generous on paper, erratic in rollout. Installers complain of stop-start funding cycles that make it difficult to build stable businesses.

The boiler question has become oddly political. Gas heating is deeply embedded in British life, both technically and psychologically. The push toward electric heat pumps is central to building decarbonisation, yet adoption remains slower than planners hoped. Grants help, but installation complexity and upfront cost still deter many households. Engineers say most homes can accommodate heat pumps with the right preparation; homeowners hear disruption and risk.

Commercial buildings are moving faster, partly because tenants and investors are applying pressure. Office landlords now talk openly about stranded assets — towers that cannot attract tenants because their energy performance is too poor. Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards have teeth here. If a building fails the rating, it cannot legally be let. That concentrates the mind. Retrofit budgets appear quickly when rental income is on the line.

Finance has started to align with policy in subtle ways. Green mortgages, sustainability-linked loans, and carbon reporting rules are reshaping how buildings are valued. A property with strong energy credentials is no longer just virtuous; it is bankable. Surveyors increasingly flag energy performance alongside structural condition. The spreadsheet is becoming a climate instrument.

Local authorities play an uneven but important role. Some councils push ahead with low-carbon planning rules, district heat networks, and area-based retrofit programs. Others struggle with staffing and funding, processing applications with minimal environmental scrutiny. The postcode lottery persists. Still, pilot projects — heat networks in dense urban zones, zero-carbon council housing — serve as working prototypes rather than theoretical models.

Grid decarbonisation has quietly made building electrification more credible. As the UK power mix has shifted toward renewables, electric heating and appliances carry a smaller carbon penalty than they once did. That interaction between sectors is easy to miss but crucial. Clean buildings depend on clean power. Policy documents acknowledge this interdependence, though delivery timelines do not always line up neatly.

There is also a skills bottleneck. Training enough installers, energy assessors, retrofit coordinators, and low-carbon heating engineers may be the least glamorous barrier to meeting targets. Trade bodies warn that targets are outpacing workforce development. A regulation is only as effective as the number of qualified people available to implement it. On some retrofit projects, the wait time for accredited contractors stretches months.

I remember standing in a newly retrofitted social housing block and being surprised by how quiet it felt once the windows were shut.

Social housing providers have, in some respects, become testing grounds. With large portfolios and long-term stewardship, housing associations can justify deeper retrofit investments. Tenants benefit from lower energy bills and improved comfort, though disruption during works can be significant. Some projects report dramatic emission cuts per dwelling, paired with measurable health improvements. Warmth, it turns out, is a public health intervention as much as a climate one.

Critics argue that the UK net zero strategy sometimes overpromises and underdelivers, particularly on funding continuity. Schemes are announced, revised, paused, and relaunched under new names. This churn erodes trust in the supply chain. Installers hire, then lay off, then hire again. Consistency might not make headlines, but it builds markets.

Measurement has improved. Smart meters, better EPC methodologies in development, and digital building management systems are generating more granular data. Large commercial sites now track energy use in near real time, adjusting lighting and HVAC minute by minute. Performance gaps — the difference between designed and actual energy use — are no longer invisible. They are graphed, audited, and sometimes penalised.

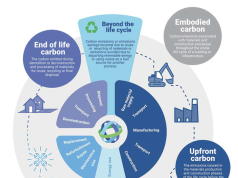

There is a design culture shift underway too. Architects increasingly talk about operational carbon and embodied carbon in the same breath. Reuse of structures — retaining frames, refurbishing instead of rebuilding — is gaining status. The greenest building, the saying goes, is the one that already exists. Once a fringe argument, it now appears in mainstream planning discussions.

The politics remain delicate. Any policy touching homes triggers scrutiny. Voters notice boiler rules faster than offshore wind targets. Governments respond by adjusting timelines, softening language, offering exemptions. The trajectory toward lower-carbon buildings continues, but rarely in a straight line. It zigzags through consultation papers and budget statements.

Progress is real, though uneven. New buildings are markedly more efficient than those built even fifteen years ago. Parts of the commercial sector are decarbonising at speed. Retrofit is expanding, if not yet at the scale required. The UK carbon targets building effort looks less like a single program and more like a layered patchwork — regulations, incentives, market pressure, and gradual cultural change stitched together.

It is not elegant. It is working more than many expected.